Empowering Change: Celebrating Women's Influence and Advancing the Future in Canadian Law

As we celebrate International Women’s Day at Illuma Law, we are taking a moment to reflect on the remarkable contributions women have made to Canada’s legal profession. Trailblazing legal minds like Clara Brett Martin, the first woman to become a barrister in Canada, and Bertha Wilson, the first woman appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1982, overcame considerable obstacles and played a pivotal role in paving a path for other women in Canada’s legal system.

While we celebrate these accomplishments, it is essential to confront a persistent challenge—the unconscious gender bias in litigation and its impact on judge-made law. We must address the urgent need for more women litigators, and thus positively influence Canadian law. Our call to action extends beyond an appreciation of women in the legal profession, to identify the barriers women in the legal field continue to face, and actively advance conversations around what needs to change in the legal profession to support women in the courtroom.

What is Judge-Made Law

Judge-made law, or case law, refers to legal principles and rules that judges develop through their decisions in individual court cases. Judge-made law differs from statutes and regulations because it evolves through the interpretation and application of legal precedents. Because judge-made law plays a crucial role in shaping the legal landscape, diverse voices must contribute to it.

Understanding the Gender Disparity in Litigation

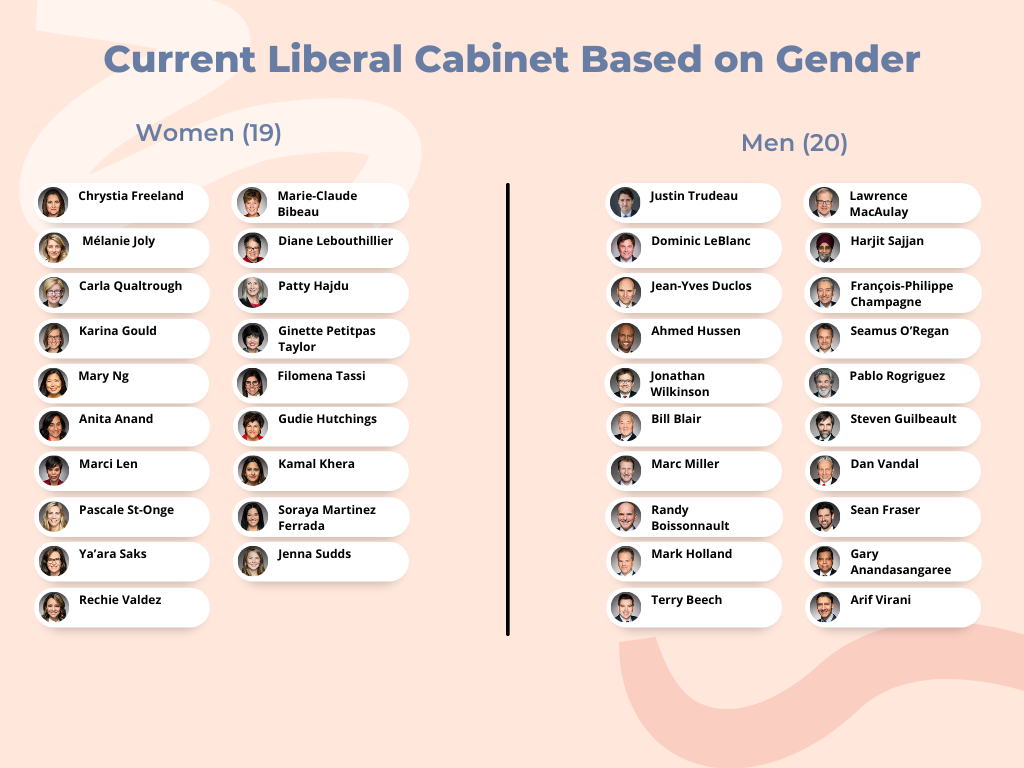

Women have made great strides in the legal profession. Recent initiatives, such as the current government’s commitment to achieving gender parity in judicial appointments, underscore the need for more inclusive legal systems. This approach highlights the understanding that diverse perspectives contribute to a fair and balanced judiciary.

Current Liberal cabinet representing 19 women and 20 men.

Supreme Court of Canada’s justices representing 5 women and 4 men.

In comparing Supreme Court Cases in 1993 and 2023, the gender of lead litigators were 1 unknown, 1 woman, and 41 men in 1993 and 1 unknown, 23 women and 48 men in 2023. The number of women litigators has increased significantly; however, there remains a glaring gender disparity in the context of litigation. The underrepresentation of women litigators in Canada has resulted in an imbalance in perspectives. The consequences of this disparity translate into a potential bias in legal doctrines, which inevitably impacts fairness and inclusivity in the legal system.

Litigators by gender comparing 1993 and 2023.

By recognizing this issue, we can explore the root causes and barriers women face to fully participating in shaping judge-made law in Canada.

The Challenge in the Structure of Litigation

Litigation is demanding, requiring extensive investment in the lead-up to a case, along with long hours spent in the courtroom. Litigation is a clear example of where the gender gap is most pronounced. Societal expectations for women combined with rigid legal practices have produced the need for women to simultaneously navigate a precarious balance between career aspirations and familial obligations. This balance often forces women to navigate additional barriers, compelling them to choose between their careers and their families.

As we confront these challenges, it becomes apparent that the lack of women litigators contributes to an incomplete and potentially biased legal framework. At the core of recognizing barriers in the legal profession is the aim to transform internal structures, empowering women to become litigators without sacrificing personal lives and aspirations.

To achieve gender parity, we must recognize and address systemic barriers that disproportionately affect women. To enable full participation of women in the legal profession, we need to challenge systemic structures that create barriers for them. The demanding hours of litigation pose challenges for women with families to fully commit to work obligations.

Solutions for Change

1. Cultural Shift in Legal Practices

One option is advocacy. Those of us in the legal profession can advocate for more flexible work arrangements to accommodate the unique demands women, and other people who are primary caregivers, face in litigation. This may require a reconceptualization of the litigation process altogether.

2. Supportive Policies and Practices

In the absence of structural changes to litigation, women may turn to support that is more piecemeal and individualized. One opportunity to support women is to facilitate mentorship of women in the legal field who are also navigating the challenge of balancing career aspirations with personal obligations. Another option is advocating for governments to provide childcare support during litigation.

3. More Representative Leadership

To achieve a more gender-diverse legal system, individual law firms may need to take the initiative to accommodate litigators within their practice. One way to do this is by promoting equal leadership and decision-making within law firms. Giving women more decision-making power can lead to cascading effects, resulting in more representation in the courtroom.

As we celebrate the contributions of women in the Canadian legal landscape, we must also acknowledge persistent disparities in litigation. Recognizing these disparities not only enables us to envision a more equitable internal legal practice, but also represents a strategic move towards a broader and more nuanced legal landscape. The call to action, empowering women litigators, is a collective responsibility that we can all contribute to at an individual and systemic level. This ensures the facilitation of a legal system reflecting diverse perspectives and lived experiences, ultimately strengthening our society.

This International Women’s Day, let's commit to building a legal landscape where all voices are heard, and justice is truly equitable for all.